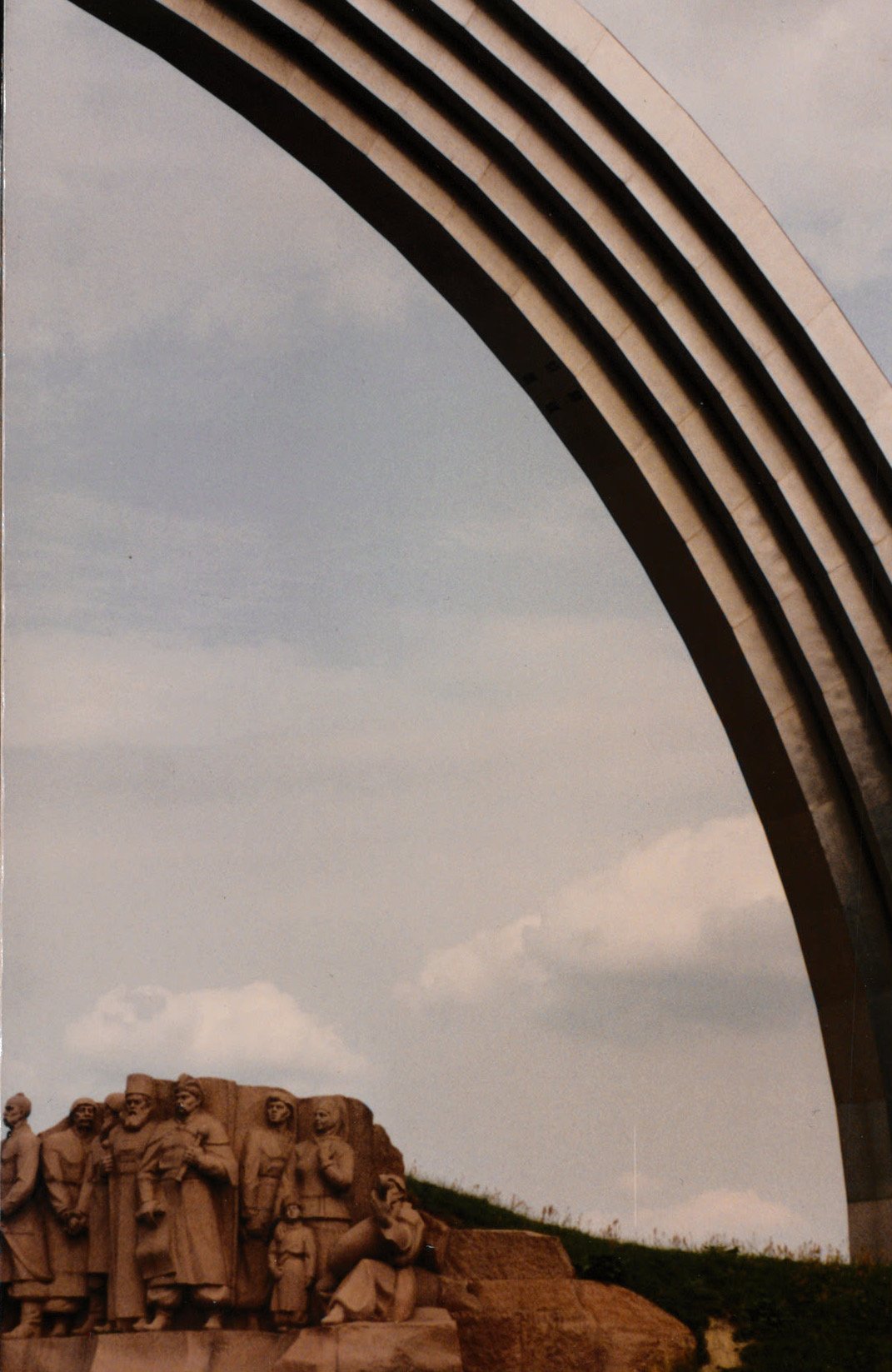

The road to Kiev

This week, our lab published a study of human memory functions. It’s also the week when Russian troops euphemistically started conducting “special operations” in Ukraine, and effectively started invading the country. The thread between these two events of arguably incommensurate amplitudes is memory.

President Putin voices his construct for the invasion of Ukraine as rooted in history. Rather, it is built on memory; his memories of a mystified past.

Brain and behavior scientists have established that memory is an imperfect process, and that memories are subjective fabrications, prone to bias and distorsions. They are the fruits of unreliable mental representations of facts and fakes. Fake memory news, in sum.

I often wonder whether public leaders are concerned by the trace they might leave in history books. If not, they should. History books are for the factual recollection of events, not memories. All forms of public authority, East and West, North and South, try to bend, to various degrees, the factual reality to their immediate or short-term advantage. Authoritarian regimes push this enveloppe further and spend a remarkable amount of time and energy bending the arrow of history until it starts pointing backwards. Authoritarian leaders also spend and consume a lot of their stamina and life points making sure history books are rewritten with ideological accounts inspired by their own memories.

This week is when President Putin has reached the apex of his history bending efforts. How he would like to be remembered in history books is his prerogative, but it’s not looking too good.

I have fond memories of Ukraine, and Russia too. I keep them with me as small pieces that patch up my personal fabric, and, yes, personal history.

Back in the spring of 1991, I took an introductory Russian college course. The classic Russian writers had propelled me through adolescence. I later discovered that some were actually from Ukraine (Gogol). I loved the melancholia, the sentiments of inescapable fate and destiny that animated their characters, often pierced violently by the bending arrow of history.

The best part of the course was an exchange program with the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute: the promises of a 2-week trip to Kiev, followed by a trip of Ukrainian students to visit us in Paris, the following semester.

I realize 1991 was 30 years ago — gosh. We boarded that beat-up Aeroflot airliner that met all our expectations: stern crew, cigarette holes in the worn out carpet and seats, clanky sound effects of uncertain origins. As many things in the East, it did the job and took us to destination.

The context of 1991 in Ukraine was historic, making our journey uncertain until the last minute. The Berlin wall had just fallen; the year before our trip, the parliament adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine, establishing the principles of self-determination and independence from USSR. The actual independence of Ukraine was declared in August 1991, a few months after our trip.

Downtown Kiev was busy with demonstrations: lots of chanting, sheer people energy, speeches out of hard-rock PA systems, lots of Ukrainian flags marching and floating. Our hosts were walking the thin line between enthusiasm and embarrassment — as if impromptu friends had showed up before they had time to put away the dirty laundry. With these beautiful slavic facial expressions of tire and disillusion, they would gently try to translate the situation for us, excited as we were of attending a moment of history.

Lots of flags indeed. US and Canadian, among others. That was before Putin saw NATO as a threat, or as an excuse. Before I was fortunate to live in both of these countries too.

This is also where I realized how the “memory of history”, again, could transform into a political weapon and an instrument of ideology. There were posters around the main square that ran a parallel between the Soviets and the Nazis — no need for translation here. Heated debates ensued, between generations of protesters. The tension between their differing perceptions of history, their subjective memories of a hurtful past that did not seize to be present to them, was palpable.

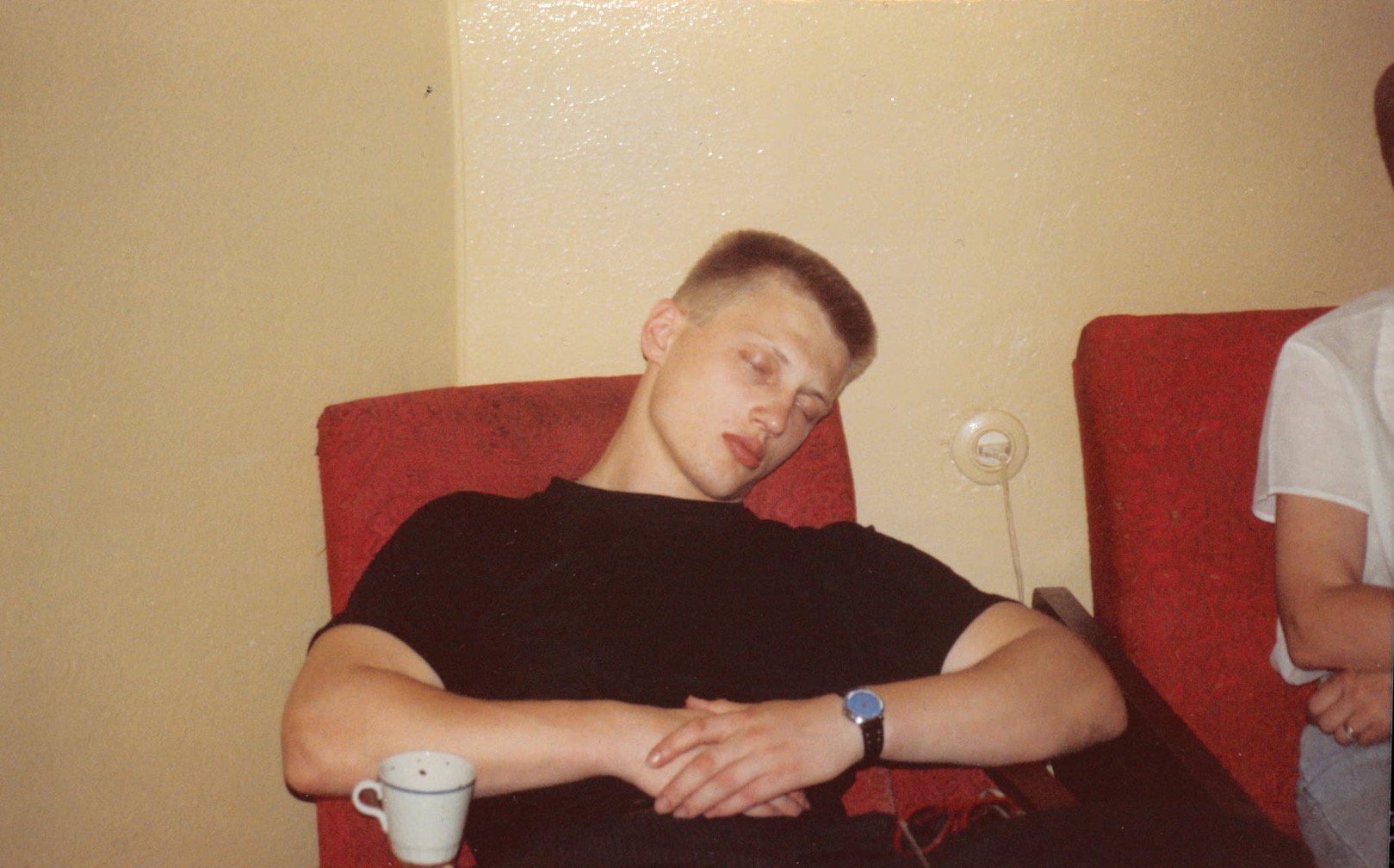

As our trip unfolded, we grew closer to our hosts: young students like us, not entirely sure of what the future was holding for them, or whether they were even allowed to share some of their anxiety with us — old protective reflexes from the vanishing Soviet era.

We went through a lot of passionate discussions though, irrigated by unlabelled vodka and the acrid smell of brown tobacco, the encaustic wood of furniture and flooring, the exaggerated rose fragrance of soap bars.

At one point, we were a small group walking late into the night across campus. I was stunned when my new Ukrainian friends started chanting La Marseillaise, the hymn of revolutionary origins — all verses (some I did not know), in perfect French, although they could not speak French.

We did field trips, deeper into the countryside: the air was hot and humid, much thicker than what I was accustomed to in France; the green from the trees and meadows much deeper too. It was not always clear which directions we were taken during those trips, and we asked, half jokingly, when was our visit to Chernobyl.

The two weeks went by and it was already time for us to leave — filled with new memories and stories, feeling more complete and grown up and richer with new friends we could not wait to welcome in Paris, six months from then. There were tears and virile hugs.

Over the next six months, we prepared what we thought was an exciting program for our exchange students friends. 1991 was pre-Internet, communication was still complicated with Eastern Europe, but overall, it seemed like back in Kiev, excitement towards this trip to France was growing too.

The exchange group travelled to Paris by bus, from Kiev (2,400 Kms), to save on costs. When we saw the bus pulling up on campus, we were just like kids jumping around.

We could not recognize the first few people that stepped out of the bus though. They were obvisouly much older than students and we thought they were professors we had not met in Kiev, for reasons we thought could be clarified later. None of the folks in the bus were students actually, and we could not even ascertain whether they were professors or administrators at the partner institution. They had brought with them loads of caviar as gifts, in jars and tin cans, stashed into the engine of the bus or hidden under the seats. The caviar tasted weird, like tar. Two days in a bus, simmered in engine oil and pestilent smokes.

The arrow of history was moving fast for Ukraine at the time. Fast like today, only in the opposite direction though. But it had not traveled fast enough yet to avoid that apparatchiks would substitute for exchange students — the generation of young Ukrainians that would forge their future democracy. A democracy on a tortuous way, and that is now threatened by the bended arrow of distorted memories.

Text & pictures by Sylvain Baillet.